He was born into a loving family but showed odd personality traits even as an infant.

But as a teenager, his behavior became increasingly unstable.

That was followed by a strange relationship with an wealthy heiress — and ultimately, a violent act that would shock an entire nation.

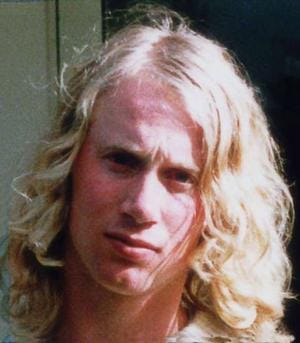

This is the story of Martin Bryant.

The calm before the storm

Little Martin entered the world with surprising ease. A calm beginning that stood in stark contrast to the chaos that would later define his life.

Martin John Bryant, weighing just six pounds (2.7 kilograms), was born on May 7, 1967, in Australia, after a labor that lasted barely two hours.

It was quick, uncomplicated, almost effortless. His father wasn’t anxiously pacing a hallway or waiting elsewhere, as many men of that era did. Instead, he stayed by his wife’s side throughout the birth.

The pregnancy itself had been just as smooth. His mother, Carleen, experienced none of the usual discomforts, no morning sickness, no swelling. She later described it as being “all baby and no fluid,” and she continued working at her job in a chocolate factory until just weeks before delivery.

Even the birth announcement reflected how ordinary everything seemed at the time. It was brief and unremarkable, reading simply: “To Carleen and Maurice. A bouncing boy. Thanks to doctor and staff.”

Nothing in those early moments hinted at what lay ahead — a reminder of how even the most unassuming beginnings can precede lives marked by darkness and loss.

The first year in Martin Bryant’s life unfolded quietly, he lived in a quiet Australian town without obvious warning signs. His mother later remembered her son as a generally happy, settled baby. She wasn’t alarmed by the fact that he resisted cuddling or showed little interest in physical affection.

But that calm didn’t last. By the time Martin was just 16 months old, he wasn’t merely walking, he was running, climbing, and constantly escaping whatever boundaries were put in place. His energy was relentless.

Frequently broke his toys

In a 2011 interview, his mother recalled that even from a very young age, Bryant was an “annoying” and “different” child who frequently broke his toys. A psychiatrist who later evaluated the boy reportedly told the family that his behavior was so disruptive and difficult that he would never be able to keep a job.

From the moment he began school, Bryant struggled with serious behavioral issues and learning difficulties. He was aggressive and destructive and found it extremely hard to relate to other children.

Locals later recalled disturbing behavior, including incidents where he pulled a snorkel from another boy while diving and cut down trees on a neighbor’s property. There are also reports that he tortured animals. He had few, if any, friends and was frequently bullied.

”I was knocked around all the time. No one wanted to be my friend,” Martin said.

By the age of 10, in 1977, his behavior had escalated to the point that he was suspended from school.

In the 1980s, Bryant returned to school, this time attending high school. A few years after leaving, he was evaluated for a disability pension by a psychiatrist who noted: ”Cannot read or write. Does a bit of gardening and watches TV … Only his parents’ efforts prevent further deterioration.”

Meeting Miss Harvey

There was, however, one person Bryant came to rely on — someone he later described as his only friend. When he was 19, he met 54-year-old Helen Mary Elizabeth Harvey, an eccentric wealthy heiress with a share in a lottery fortune, while he was seeking new customers for his lawn-mowing business.

He helped with various tasks around her home, including feeding the fourteen dogs living in the mansion and the forty cats kept in her garage. According to reports, he behaved towards Miss Harvey like an affectionate, obedient and helpful child.

In 1991, after Bryant was no longer allowed to keep animals at the mansion, he and Helen Mary Elizabeth Harvey moved to a 29-hectare (72-acre) farm called in a small town of Copping, on Tasmania in Australia.

Neighbors soon noticed Bryant’s unsettling behavior: he always carried an air gun and was often seen firing at tourists who stopped to buy apples at a highway stall. Late at night, he would roam nearby properties, shooting at dogs that barked at him. Locals later said they avoided Bryant “at all costs,” despite his attempts to befriend them.

Tragedy struck on October 20, 1992, when Harvey was killed in a car crash along with two of her dogs. The car veered onto the wrong side of the road and collided head-on with an oncoming vehicle. Bryant was in the car at the time and suffered severe neck and back injuries, keeping him hospitalized for seven months. After leaving the hospital, he returned to his family home to recover.

Police briefly investigated Bryant’s role in the accident, noting his history of lunging for the steering wheel and the fact that Harvey had already been involved in three previous accidents.

Bryant was named the sole beneficiary of Harvey’s will, inheriting assets worth several million dollars. He spent part of his inheritance on trips abroad, visiting cities like London, Los Angeles, Amsterdam, and Bangkok.

“I wanted to meet up with normal people” but “it didn’t work,” Bryant said. According to him, the highlight of the trips was the long plane rides, where he could talk to the people beside him and they could not move away.

The mysterious death of his father

After Miss Harvey’s death, Bryant’s father, Maurice, 60, took over running the farm where his son and the older female companion had lived. But Maurice’s life would soon also end tragically. In the summer of 1993, a visitor looking for Maurice at the property found a note pinned to the door reading “call the police” and discovered several thousand dollars left in his car.

Authorities searched the property but could not locate Maurice. Reports say Bryant even joked and laughed with police while they were searching the property.

Divers were then called to investigate the four dams on the land, and on August 16, Maurice’s body was recovered from the dam nearest the farmhouse, with a diving weight belt around his neck. Police described the death as “unnatural,” and it was officially ruled a suicide.

Bryant then inherited the proceeds of his father, around $160,000.

Isolated and drunk

With the deaths of both Miss Harvey and his father, Bryant grew increasingly isolated. But with his newfound wealth, the young man started amassing a large collection of firearms. At the same time, he also began drinking heavily. Reports estimate his daily intake included about half a bottle of Sambuca and a full bottle of Baileys Irish Cream, along with port wine and other sweet alcoholic beverages.

Even though it was clear that Bryant was on a slippery slope, no one could have predicted the day he would erupt in violence.

On April 28, 1996, Martin Bryant unleashed a deadly rampage that would leave an indelible mark on Australia’s history, a day that would become known as the Port Arthur Massacre.

Having spent part of his childhood at his family’s beach house in Carnarvon Bay, which sits near the Port Arthur Historic Site, Bryant was very familiar with the area.

Port Arthur, the site of the massacre, is a historic former 19th-century penal colony that had been turned into an open-air museum.

Horrific rampage

On the morning of April 28, 1996, Martin Bryant began his horrific rampage at the Seascape guesthouse in Port Arthur, where he shot the owners before casually walking over to the Broad Arrow Café to order lunch.

Moments later, he pulled out a Colt AR-15 rifle and fired on diners, killing 12 people in just 15 seconds, the start of the deadliest mass shooting in Australia’s history.

Ian Kingston, a security guard at Port Arthur, saw Bryant open fire and immediately dived for cover, shouting at visitors outside to flee.

Many tourists initially dismissed the gunfire as part of a historical reenactment until Kingston’s urgent warnings made them realize the danger.

“You don’t get a second chance with a gun like that,” he later said, explaining why he didn’t attempt to confront Bryant inside the café.

Bryant’s violence didn’t stop there. After the café, he moved on to the gift shop, killing eight more people, and then continued firing at tour buses in the parking lot.

By the time he returned toward the guesthouse, he had murdered 31 people and taken a hostage. Kingston later questioned his own actions during the chaos:

“Should I have waited until he came out? Should I have tried to tackle him? Did I do the right thing? Would I have saved more lives if I tried to tackle him rather than get people away from the front of the cafe?”

The tragic death toll

The massacre lasted only 22 minutes, but bringing Bryant to justice took much longer. Police quickly surrounded the Seascape guesthouse, aware that he was armed and holding a hostage, though unsure if others were inside. Officers Pat Allen and Gary Whittle hid in a ditch with a clear line of sight to the house for eight tense hours. Bryant refused to surrender, and after 18 hours, he set the guesthouse on fire, accidentally igniting himself in the process.

Special operations commander Hank Timmerman recalled, “He set the place on fire and consequently set himself on fire as well … so we had to extinguish him as well as arrest him.” Tragically, the hostage was killed, bringing the total death toll to 35.

The Port Arthur massacre had a seismic impact on Australia’s gun laws. In 1987, the New South Wales premier had ominously predicted, “It will take a massacre in Tasmania before we get gun reform in Australia.”

That grim prediction became reality. Within days, Prime Minister John Howard announced sweeping reforms banning automatic and semi-automatic long guns, introducing strict licensing rules, and launching a nationwide gun buyback program that ultimately destroyed 650,000 firearms.

The buyback alone cut firearm suicides by 74%, saving an estimated 200 lives each year.

Why did he do it?

As for Bryant, he pleaded guilty to 35 counts of murder and received life imprisonment without the possibility of parole. He is still serving his sentence at Risdon Prison, a maximum-security facility near Hobart, Tasmania.

Over the years, Bryant has given inconsistent and muddled explanations for why he killed 35 people. It may have been driven by a craving for attention, as he reportedly told a next-door neighbor, ”I’ll do something that will make everyone remember me.”

Reflecting on Australia’s response to the tragedy, former deputy prime minister Tim Fischer said, “Port Arthur was our Sandy Hook. Port Arthur we acted on. The USA is not prepared to act on their tragedies.”

In the wake of the Bondi Beach terror attack in December 2025, Australia’s gun laws have come back into the spotlight. One of the shooters, Sajid Akram, held a category AB firearm license, which legally allowed him to possess six guns, according to the NSW Police Commissioner.

This license, granted for “recreational” purposes, allowed him an unlimited number of certain rifles and shotguns. Footage from the attack shows Akram and his son equipped with at least a shotgun, two precision rifles, and ammo belts.

NSW Police are still investigating whether all six weapons found at the scene were registered to Akram.

While it may look like a serious arsenal, six firearms is actually fairly standard for an Australian gun owner. In 2024, gun licensees in Australia owned an average of 4.3 guns each, according to research from the Australia Institute. Across the country’s 943,000 license holders, there were around 4 million guns, and some individuals had hundreds.

“In the years since the Port Arthur shooting..”

“There are two individuals in inner Sydney who own over 300 firearms each,” the report notes. “Owning this many guns is legal under firearm laws in all states and territories except WA.” Western Australia recently introduced stricter gun laws, including limits on the number of firearms per licensee.

Forensic firearms expert Gerard Dutton told the ABC that the way the shooter in Bondi Beach was reloading, “with a manual action between each shot, reveals it to be a variation of a ‘bolt-action’ rifle with a ‘straight pull action.’”

Dutton also noted that the gun market has evolved since semi-automatic weapons were banned after the Port Arthur massacre in 1996:

“In the years since the Port Arthur shooting, when the new laws were implemented and semi-automatic actions banned, variations in the common types of manually operated firearms entered the market that bridge the gap between traditional manual repeaters and semi-automatic weapons.”

The debate over gun laws and who should have access to high-powered firearms is set to continue in Australia, just as it does around the world, especially in light of the victims of mass shootings, which starkly highlight the devastating consequences of some weapons.

As we reflect on these tragedies, our thoughts go out to all the innocent lives lost — the victims whose stories were cut tragically short, and the families forever changed. May we honor their memory by remembering them, learning from these events, and striving for a safer future.